Professor David Norman, bye-Fellow of Christ’s College, has explained a gap in the dinosaur family tree by showing that ‘bird-hipped’ dinosaurs likely evolved from a group of animals called silesaurs.

The origins of ‘bird-hipped’ dinosaurs – also known as ornithischians – have puzzled researchers for many years and a 25-million-year gap in the fossil record makes it difficult to identify the branch of the family tree to which ornithischians belong.

Professor Norman said

“Evolutionary theory predicted that ornithischians originated with all other dinosaurs in the Late Triassic but exhibited a unique set of features that could not be fitted into a neat evolutionary succession from their dinosaur cousins.

In point of fact, during the Late Triassic - from 225-200 million years ago no ornithischians have been discovered, anywhere. There is an ‘ornithischian gap’ in the fossil record and then suddenly about 200 million years ago ornithischians appeared, as if out of nowhere.”

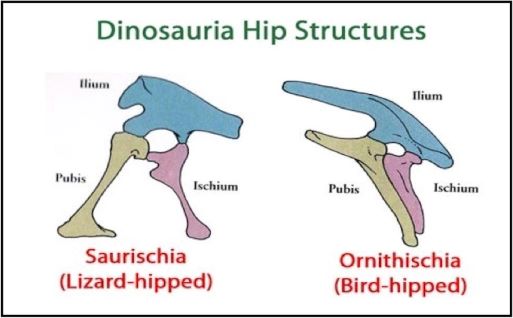

Historically, the classification of dinosaurs was based on the shape of their hip bones: either as saurischians (‘lizard-hipped’) such as Tyrannosaurus and Diplodocus, or ornithischians (‘bird-hipped’) such as Triceratops and Iguanodon.

This classification system, developed by Cambridge-trained Harry Seeley, and first published in 1888, proved to be both simple and useful: all dinosaur discoveries appeared to fit into one of these two groupings.

But in 2017 Professor Norman, of the Department of Earth Sciences, argued that this fundamental classificatory scheme needed to be reassessed in the light of new discoveries and a technical reassessment of the shape of the dinosaur family tree.

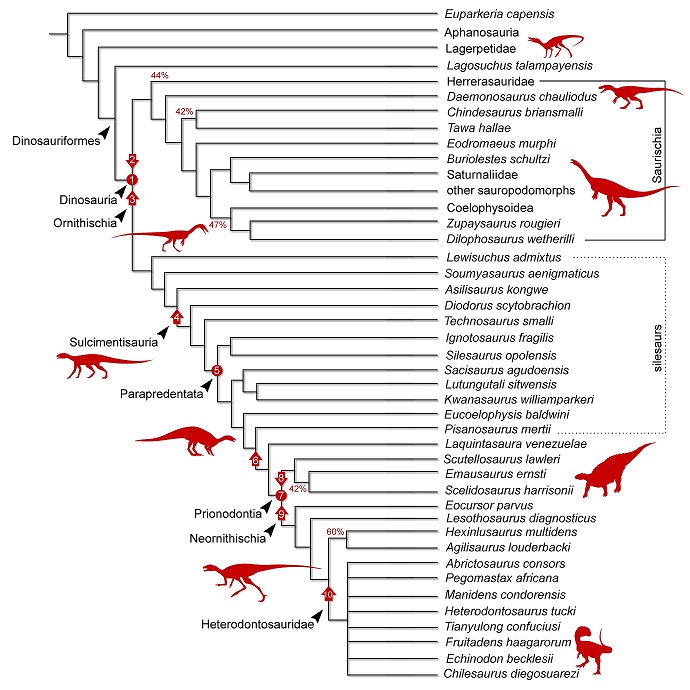

More recently, further work on the shape of the dinosaur family tree has been directed toward resolving the origins of the Ornithischia.

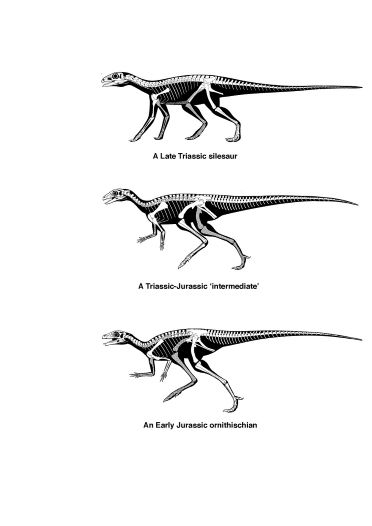

One particularly interesting discovery lay largely unappreciated for almost two decades; this was the discovery of a dinosaur-like animal, described and named Silesaurus (‘Silesian lizard’) in 2003. Many researchers suggested that silesaurs were quite close relatives of true dinosaurs. In 2020, scientists from the Universidade Federal de Santa Maria in Brazil proposed that silesaur-like creatures might sit on the branch of Dinosauria that led to Ornithischia.

The team in Brazil began a collaboration with Professor Norman’s team in Cambridge and their combined research has produced a family tree that depicts silesaurs as a succession of animals on the stem of the branch leading to Ornithischia.

Silesaurs are ‘lizard hipped’ but have a toothless, beak-like region at the front of the lower jaw, which is very similar to the toothless, beak-like structure known as a ‘predentary’ found in true ornithischian dinosaur skulls.

Careful analysis of a variety of silesaurs allowed Professor Norman and colleagues to argue that the unique anatomical characteristics typical of traditional ornithischians are the result of the progressive modification of those seen in silesaurs. This evolutionary transformation took place during an interval of about 25 million years, during the Late Triassic Period. By the end of this interval (in the earliest Jurassic Period – about 200 million years ago) recognisable ornithischians had finally evolved.

This pattern of evolution has a complicating aspect in that as the earliest ornithischians, silesaurs had none of the anatomical characteristics of their true ornithischian descendants: they lacked a predentary bone and retained the ‘lizard hip’ construction – so they were technically saurischian.

Professor Norman said

“From a taxonomic perspective, classifying silesaurs as early ornithischians seems counterintuitive. But, taking a Darwinian perspective, the unique anatomical characteristics of ornithischians had to evolve from somewhere, and where better than from their nearest relatives: their saurischian cousins!”

Reference:

David B. Norman et al. ‘Taxonomic, palaeobiological and evolutionary implications of a phylogenetic hypothesis for Ornithischia (Archosauria: Dinosauria).’ Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (2022). DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlac062