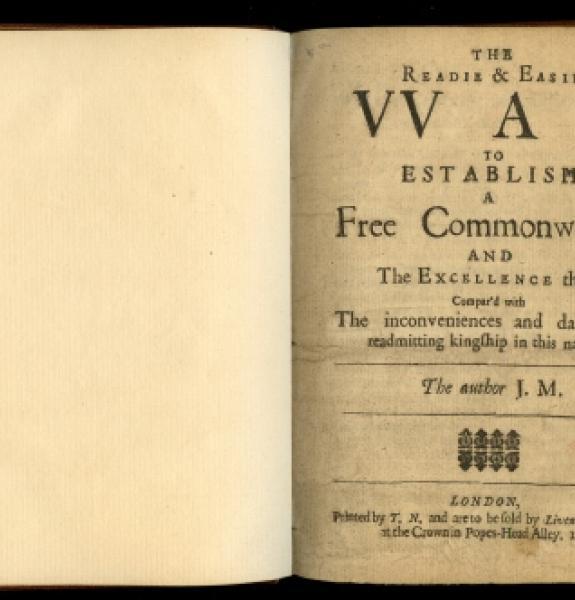

Against the Bishops

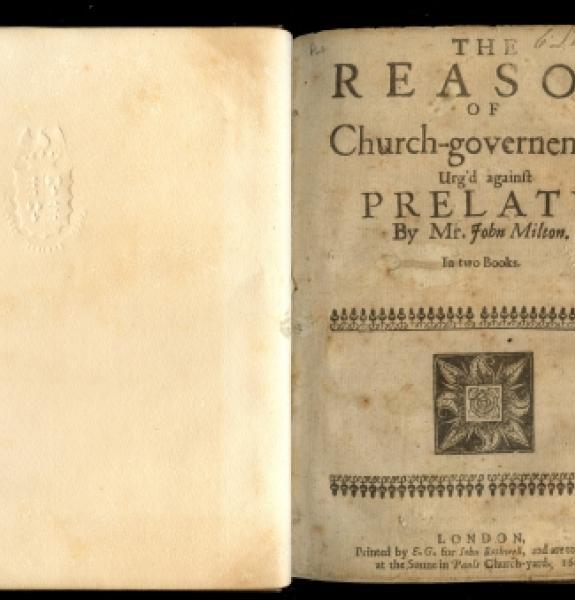

When Milton returned from his European travels in 1639, he found an England divided around the reported excesses of its king. Charles’s deeply unpopular archbishop, William Laud, was, furthermore, perceived to be steering the English Church dangerously close to Catholicism. Milton’s anticlerical instincts drove him to fire off a series of pamphlets on the side of church reform. These early tracts, which include Of Reformation (1641) and The Reason of Church Government (1642), demand an end to ‘prelaty’—that is, the hierarchical government of the church by bishops. They are the opening salvo in Milton’s lifelong battle for religious and political freedom.

Click on the images below for more details.

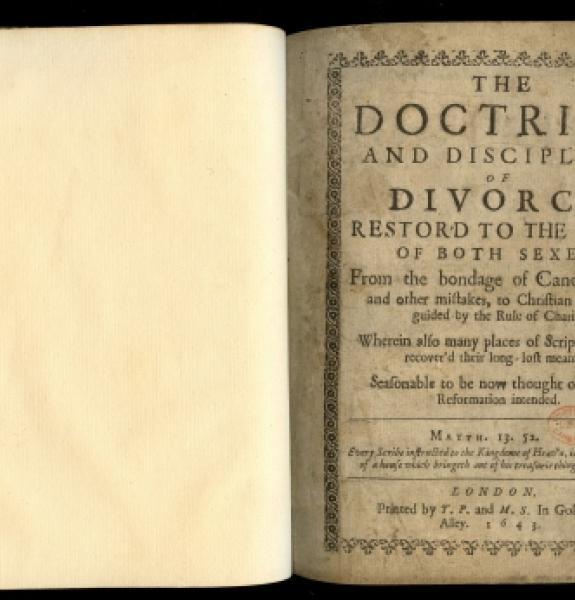

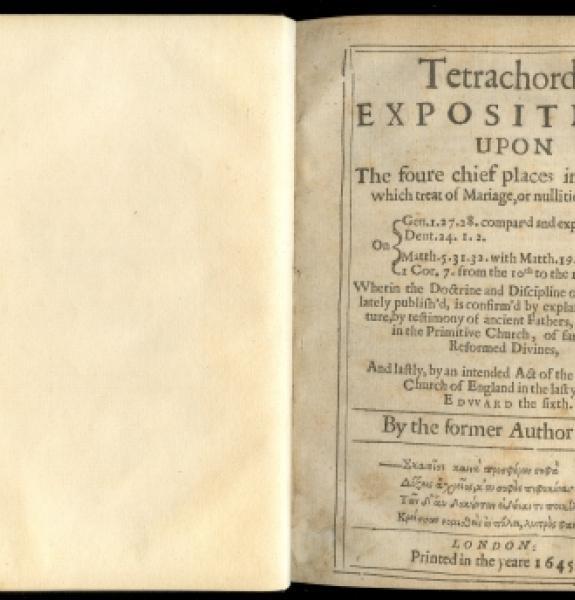

In May 1642, Milton married the 17-year-old Mary Powell. After only a month of marriage she ran back to her parents’ house in Oxfordshire and for three years resisted Milton’s pleas to return. Marked by this personal experience of marital unhappiness, Milton published a series of tracts from 1642-45 arguing for the option of divorce on the basis of ‘indisposition, unfitnes, or contrariety of ‘mind’. His radical ideas anticipated the concept of ‘irretrievable breakdown’, which was only adopted into English law in 1977.

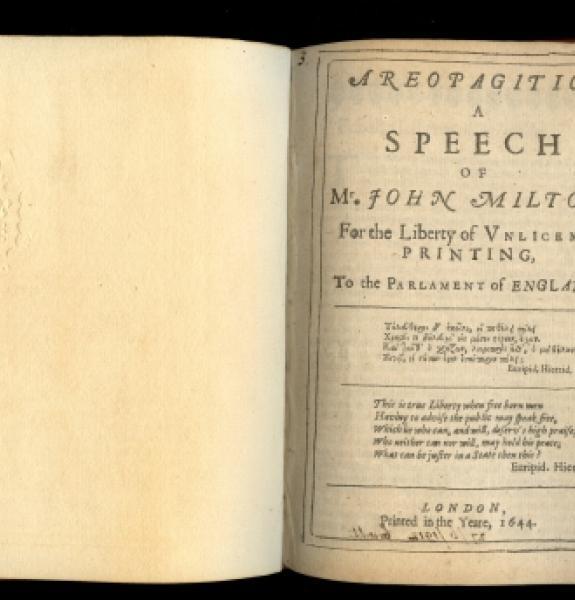

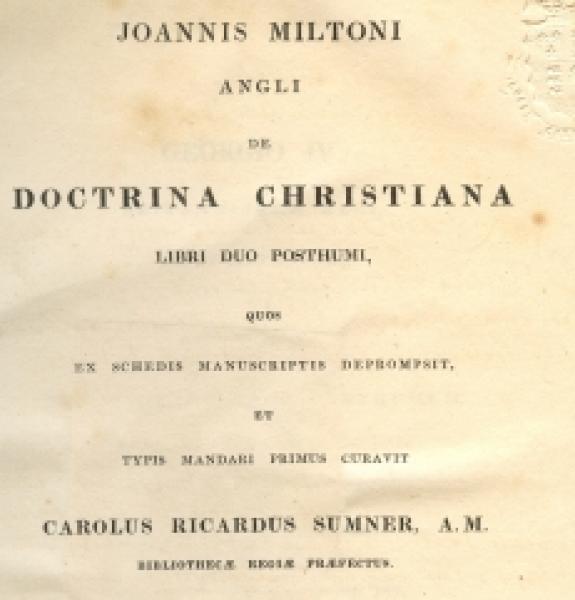

Milton’s most important work of political prose, Areopagitica (1644), was written in response to government attempts to censor what it considered the dangerous and irreligious views Milton expressed in his earlier pamphlets. Milton believed that individuals can reach the truth only by forming their own judgments: it is necessary to sift through evil in order to comprehend good. On basis he argues for freedom of speech and debate, but, significantly, excludes Catholic propaganda from this particular liberty.

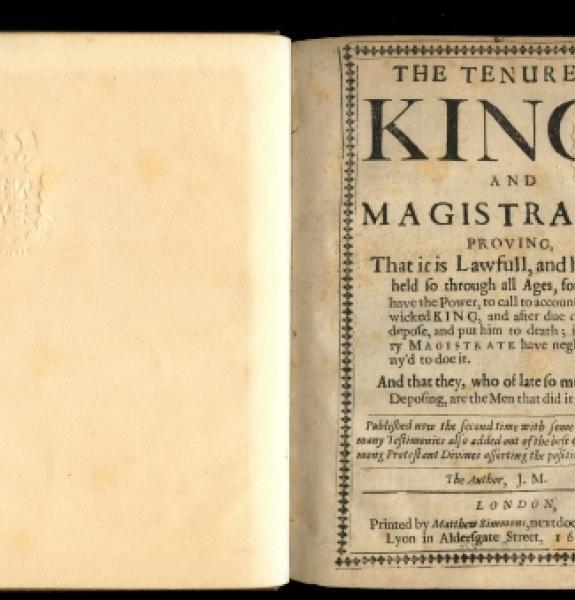

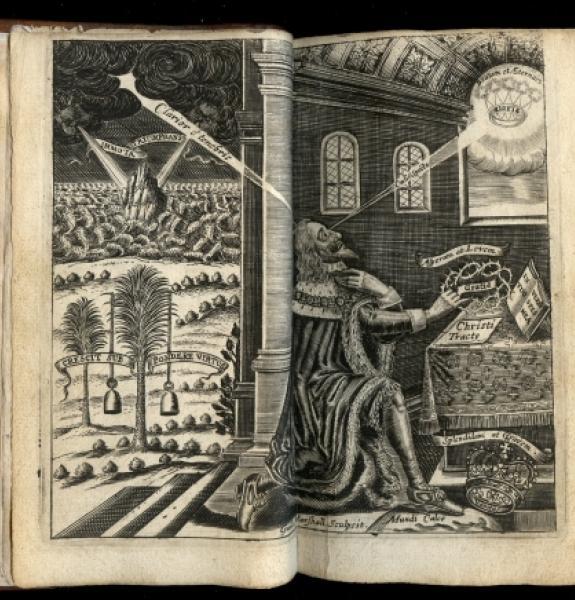

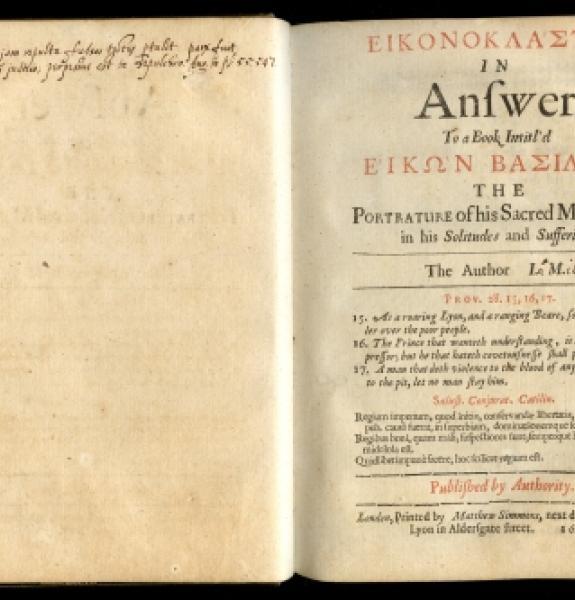

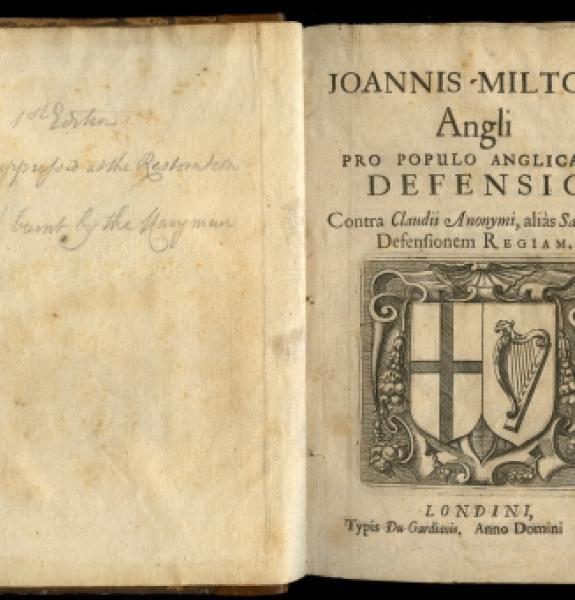

On 30 January 1649 Charles I was executed and the English Republic established under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell. That March, Milton was appointed Secretary for Foreign Tongues, a post in the new administration. Milton’s first task was to write a response to Eikon Basilike (‘image of the king’). This collection of meditations and prayers, purporting to have come from the pen of the late king himself, was released within days of his execution and became an overnight publishing sensation. Milton’s riposte, Eikonoklastes (‘breaker of images’), a bitter, point-by-point debunking of Charles’s pretensions to martyrdom, hit the presses by autumn. Upon the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, this book alone was sufficient to ensure Milton’s arrest and imprisonment.